Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Humans aren’t the only ones on the virtual reality craze. Scientists have just debuted a new technology that allows rats to more realistically—and adorably—experience VR in the lab.

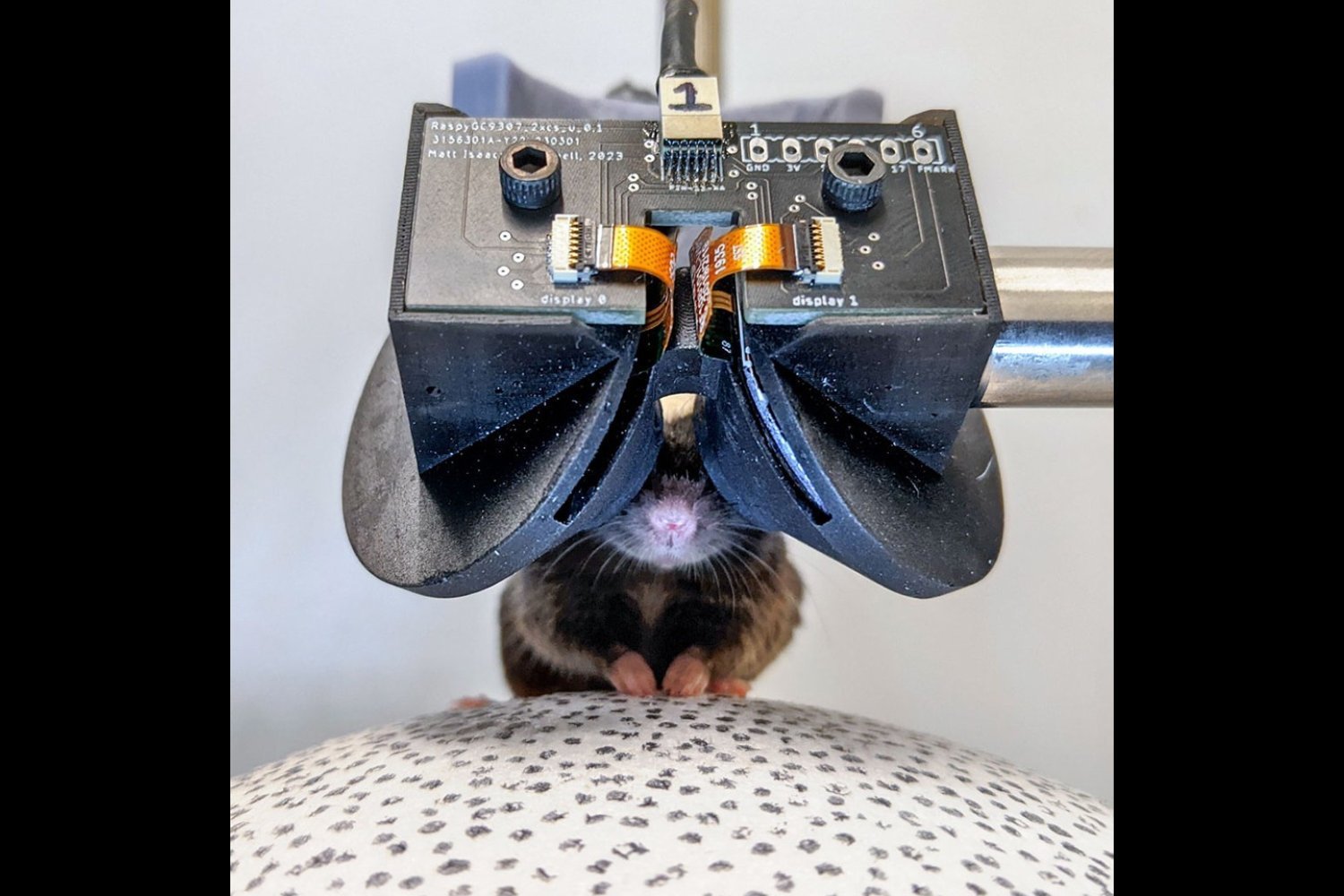

Cornell University researchers developed the technology, which they aptly named MouseGoggles. In experiments with rats, rats responded vividly to simulated stimuli while wearing the goggles. The innovation will make it easier for scientists to conduct animal studies involving VR.

As fun as the concept of mouse VR sounds, there are real applications for it. Ideally, VR could allow scientists to simulate the natural environment for mice under more controlled conditions. Right now, though, the most commonly used set-ups are pretty clunky, with rats often placed on a treadmill while they’re surrounded by a computer or projection screen. These screens cannot cover a mouse’s entire field of view, and animals can take a long time to react to the VR environment, if they ever do.

The Cornell researchers think their MouseGoggles are a significant step up from standard mouse VR. Instead of trying to build a mini-Oculus Rift from scratch, they built their system using tiny, low-cost parts borrowed from smartwatches and other existing devices. As with other VR systems, mice are placed on a treadmill to use mousegoggles. Their heads are held still with goggles while feeding visual stimuli.

“It certainly benefited from the hacker principle of taking parts that were built for something else and then applying it to some new context,” said lead scientist Matthew Isaacson, a postdoctoral researcher at Cornell. to say The Cornell Chronicle, a university news outlet. “The perfectly sized display, as it turns out, is already made for smartwatches for a mouse VR headset. We were lucky that we didn’t have to build or design anything from scratch, we could easily source all the cheap parts we needed.”

To confirm the effectiveness of their system, the researchers exposed the mice to various stimuli, all the while measuring their brain activity and observing their behavior. Across a series of experiments, the researchers found that the rats actually saw and responded to VR as expected. In one condition, for example, they tracked how mice responded to a slowly approaching dark spot that might represent a potential predator.

“When we tried this type of experiment in a typical VR setup with a large screen, the mice didn’t react at all,” Isaacson said. “But almost every mouse, the first time they look through the goggles, they jump. They have a huge shocking response. They really thought they were being attacked by a predator on the prowl.”

The team was searching published earlier this month in the journal Nature Methods.

Developing more realistic VR for mice could have all kinds of benefits down the road, the researchers say. Accurate VR experiments could allow scientists to better map and understand brain activity in mice modeled for Alzheimer’s, for example, specifically in areas tied to spatial navigation and memory; This could improve basic research studies testing potential treatments for brain disorders.

Isakson and his colleagues aren’t the only researchers who have Recently created VR system for mice. But they say theirs is the first to include eye and pupil tracking. And they’re already developing a lightweight, mobile VR set-up that can be used with rodents as large as mice or tree trunks. They hope to include more upgrades in future iterations, such as finding ways to simulate taste and smell.