Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

It was declared as the year of democracy. With more than one and a half billion votes cast in 73 countries, the 2024 election offers a rare opportunity to take the social and political temperature of nearly half the world’s population.

The results are in now, and they have given a damning verdict on public appointments.

In the year In each of the 12 developed Western nations holding national elections in 2024, incumbents lost their share of the electoral vote, the first time this has happened in 120 years of modern democracy. In Asia, even the hegemonic governments of India and Japan were not spared from the evil winds.

Incumbent and otherwise, the centrist won, as voters fell behind extreme parties on both sides. The populist right in particular has surged forward, largely due to a real shift among young men.

The results paint a picture of voters angered by high inflation, fed up with the recession, worried about rising immigration and generally disillusioned with the system.

In the year of democracy, there was an outcry that democracy was no longer working, and the younger generation, many of whom voted for the first time, delivered some harsh rebuke to the institution.

On average in developed countriesIn the year In 2024, incumbent vote share fell by seven percentage points, an all-time record and more than doubling since the global financial crisis when voters castigated elected officials.

Countries with similar results point to a common eclipse.

In the year Coming to 2024, high and inflation was the main concern of the people in most of the countries going to the polls. Failures are not very popular, but their impact is unevenly distributed. Inflation makes everyone angry.

But if the cost of living is found to be a handicap to incumbents, a closer look at the various countries and regions reveals that frustration is far from the only cause.

The biggest opposition to the sitting government came in Britain, where the Conservative charge sheet included not only high prices but also a corruption scandal, a crisis in public health care provision, a self-inflicted economic shock and a sharp rise in immigration.

Across the French Channel, President Emmanuel Macron’s attempt to secure popular rights by calling snap legislative elections has failed. The resulting political chaos could not be fully resolved months later.

In India, Narendra Modi’s formidable Bharatiya Janata Party machine has lost its parliamentary majority as it struggles to stem the tide of discontent created by a growing disconnect between strong economic growth and weak job creation.

This is particularly evident among the youth, where the unemployment rate has risen to nearly 50 percent ahead of the election, according to data from the Indian Economic Monitoring Center.

Even compared to other central themes in the year’s political shifts, exceptions to the anti-incumbency wave are rare.

In Mexico and Indonesia respectively, Claudia Schinbaum and Prabowo Subianto each improved on the presidential margin. In both cases, they ran massive campaigns pledging to continue with their anti-elitist predecessors, marking the overall success of the populists in the past twelve months. Prabowo also leaned on the new supremacy. social media Landscape, another common theme.

Globally, the poor performance of centrist parties and populist rallies, particularly on the right, was as strong a theme as the anti-incumbency wave, perhaps even stronger.

The victory of the Labor Party in Britain this year is no different, with less votes than the two elections. In the months since the victory, opinion on both the party and the leader has changed dramatically.

The French public’s disenchantment with Macron and his centrist party reflects a broader global sense of disillusionment with the political establishment. Elected officials Either ordinary people don’t know what to think or they don’t care.

Although the eventual victory was narrower than expected, France’s National Assembly’s 15-point margin in parliamentary elections was the largest of any developed country this year. The second, third and fourth biggest gainers of the year are all right-wing populists in the form of Austria’s Freedom Party, Britain’s Reform UK and Portugal’s Chega.

This shows that migration has become a concern in developed countries in recent years and was one of the key issues on voters’ minds when they went to the polls.

While conservative parties have lost ground, the main beneficiaries have been parties on the general right. Nigel Farage’s reforms have succeeded in unseating Britain’s conservative voters by failing to deliver on promises to reduce immigration.

But the anti-establishment achievements were not limited to the right. The Greens were one of the most popular radical left-wing parties in the UK, with voters disillusioned with the center on both sides.

While the timing and magnitude of the countervailing wave is primarily indicative of a short-term price shock, population growth appears to be continuing—or perhaps accelerating. Trend It has been playing in more and more countries for at least two decades.

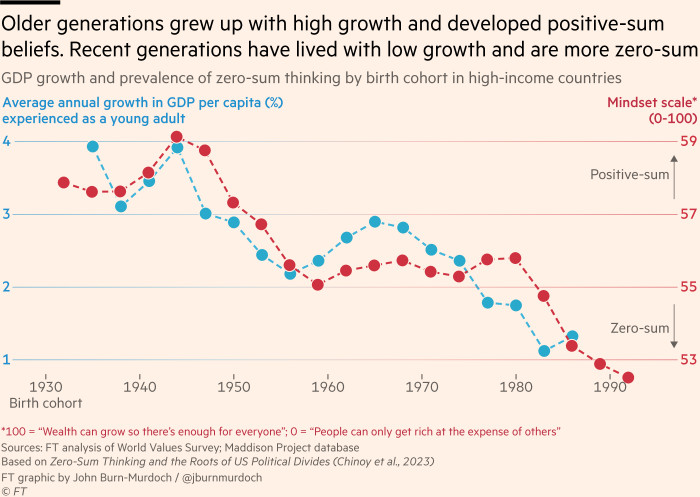

A popular theory as to why we see this is placed in the influencer Paper A group of Harvard economists published earlier this year found that people who grow up against a background of weak economic growth and low intergenerational progress are more likely to see the world as a zero sum, in which one person’s benefit must be someone else’s. Cost.

A steady decline in upward economic activity Rich countries So it can explain much of what is in these views, which They tend to bond. For parties and politicians on the left and right who promise to tear apart the existing order or protect foreign threats.

One more chance Dramatic changes in the media landscape over the past two decades have played a role in eroding previously long-standing public discourse and talking points. The emergence of social media has created an environment for non-politicians to speak directly to the public, leveling the playing field in favor of previously established individuals and parties.

underground Among the headline results, one of the most striking patterns across countries is support for the populist right among young men.

In Britain, support for reform is now higher among men in their late teens and early twenties than among men in their thirties, and a significant gender gap has opened up among young voters. A similar pattern can be seen in the US, with young people swinging heavily to Donald Trump in November, and a similar pattern can be seen in much of Europe.

Notably, this trend seems to have a lot of room to continue: the share of those who say they would consider voting for the far right is higher than it used to be.

Such a clear change is very alarming, but not without a convincing explanation. If dissatisfaction with economic stagnation drives zero-sum attitudes, few groups experience such deprivation, as do young men of their relative socioeconomic status. Permanent failure on the west side.

But it is not only young people who go to extremes. Young women in the US also turned to Trump, while in the UK they shifted heavily to the Greens.

It agrees with this. Research Earlier this year, data from polling firm Focal Data found that young people were more likely than their elders to support a hypothetical national populist party, and 2020 study In the developed West, democracy is declining faster among young adults than any other group.

All are displays Both 2024 trends are set to continue next year. Recent polls show that the governments of Australia, Canada, Germany and Norway may lose power in the coming months.

And it’s the populist right again that seems poised to make big gains in most of these countries. Norwegian right-wing populist Progress party While finishing fourth in 2021, he is currently in second place in Germany’s AfD polls.

The acute inflation problem may be over, but with stubbornly weak economic growth, a widening generational wealth gap, and a fragmented media, 2024 may be a point less of a problem, especially if the trend is downward.