Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The BBC

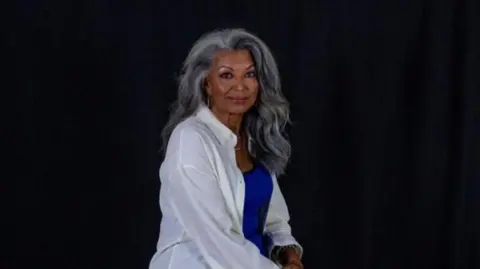

The BBCShirley Chung was just one year old when she was adopted by a family in the US in 1966.

Born in South Korea, her birth father was a member of the US Army who returned home soon after Shirley’s birth. Unable to cope, her birth mother placed her in an orphanage in the South Korean capital of Seoul.

“He abandoned us, that’s the nicest way I can put it,” says Shirley, now 61.

After about a year, Shirley was adopted by a couple from the US who took her back to Texas.

Shirley grew up leading a life similar to that of many young Americans. She went to school, got a driver’s license and worked as a barmaid.

“I was moving, breathing and having problems like many American teenagers of the 80s. I’m a child of the 80s,” says Shirley.

Shirley has children, marries and becomes a piano teacher. Life went on for decades with no reason to doubt her American identity.

But then in 2012, her world came crashing down.

She lost her social security card and needed a new one. But when she went to her local Social Security office, Shirley was told she had to prove her status in the country. She eventually found out that she did not have American citizenship.

“I had a bit of a mental breakdown when I found out I wasn’t a citizen,” she says.

Shirley Chung

Shirley ChungShirley is not alone. Estimates of how many American adoptees are stateless range from 18,000 to 75,000. Some foreign adoptees may not even know they do not have US citizenship.

Dozens of adoptees have been deported to their home countries in recent years, according to the Adoptee Rights Law Center. A man born in South Korea and adopted as a child by an American family – only to be deported to his homeland because of a criminal record – took his own life in 2017.

The reasons why so many adopted children in the US are stateless are varied. Shirley blames her parents for failing to finalize the proper paperwork when she came to the US. She also blames the school system and the government for not emphasizing that she is stateless.

“I blame all the adults in my life who literally just dropped the ball and said, ‘She’s here in America now, she’s going to be okay.’

“Well, am I? Am I going to be okay?”

Photo provided

Photo providedAnother woman, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of attracting the attention of authorities, was adopted by an Iranian-American couple in 1973 when she was two years old.

Growing up in the US Midwest, she encountered some racism, but generally had a happy upbringing.

“I settled into my life always knowing that I was an American citizen. That’s what I was told. I still believe that today,” she says.

But that changed when she tried to get a passport at the age of 38 and discovered that immigration authorities had lost important documents that supported her claim for citizenship.

This further complicated her feelings about identity.

“I don’t personally categorize myself as an immigrant. I didn’t come here as an immigrant with a second language, a different culture, family members, ties to the country I was born in… my culture was erased,” she says.

“They tell you that you have these rights as an American — to vote and participate in democracy, to work, to go to school, to raise your family, to have freedoms — all these things that Americans have.

“And then all of a sudden they started pushing us into the immigrant category simply because we were cut out of the legislation. We were all supposed to have the same citizenship rights because that was promised through the adoption policies.”

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesFor decades, intercountry adoptions approved by courts and government agencies did not automatically guarantee U.S. citizenship. Adoptive parents sometimes fail to secure legal status or naturalized citizenship for their children.

The Child Citizenship Act of 2000 made some progress in correcting this, granting automatic citizenship to international adoptees. But the law only covered prospective adoptees, or those born after February 1983. Those who arrived before then were denied citizenship, leaving tens of thousands in limbo.

Advocates pushed for Congress to remove the age limit, but those bills failed to pass the House.

Some, like Debbie Principe, whose two adopted children have special needs, have spent decades trying to secure citizenship for their dependents.

She adopted two children from an orphanage in Romania in the 1990s after watching them in Shame of a Nation, a documentary about the neglect of children in orphanages after the Romanian revolution of 1989, which caused shock around the world when it aired.

The most recent denial of citizenship came in May and was followed by a notice stating that if the decision was not appealed within 30 days, she would have to turn her daughter over to Homeland Security, she said.

“We’ll just be lucky if they don’t get caught and deported to another country that’s not even their country of origin,” Ms Principe said.

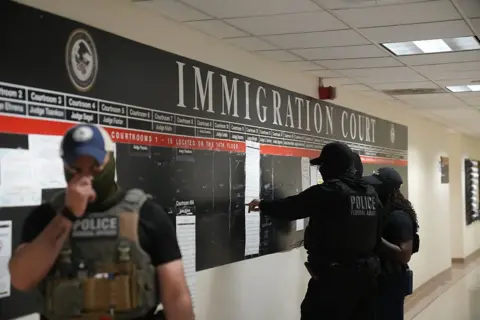

Reuters

ReutersThose fears for adoptees and their families have grown even more since President Donald Trump returned to the White House, pledging to remove “immediately all aliens who enter or remain in violation of federal law.”

Last month, the Trump administration said “two million illegal aliens have left the United States in less than 250 days, including an estimated 1.6 million who have voluntarily deported themselves and more than 400,000 deportations.”

Although many Americans support deporting illegal immigrants, there has been uproar over some incidents.

In one case, 238 Venezuelans were deported from the US to a maximum security prison in El Salvador. They were accused of being members of the Tren de Aragua gang although most of them have no criminal records.

Last month, US officials detained 475 people – more than 300 of them South Korean citizens – who they said were working illegally at Hyundai’s battery plant, one of Georgia’s largest foreign investment projects. The workers were taken away in handcuffs and chains to be detainedcausing outrage in their home country.

Adoptee rights groups say they have been inundated with requests for help since Trump’s return and some adoptees have gone into hiding.

“When the election results came out, it started really flooding in with requests for help,” said Greg Luce, an attorney and founder of the Adoptee Rights Law Center, adding that he received more than 275 requests for help.

The adoptee, who arrived from Iran in the 1970s, said she has started avoiding certain areas, such as the local Iranian supermarket, and shares an app with her friends so they can always access her location in case she is “swept away”.

“At the end of the day, they don’t care about your background. They don’t care that you’re here legally and it’s just a paperwork error. I always tell people that this one piece of paper basically just ruined my life,” she said.

“As for me right now, I feel stateless.

The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to a request for comment.

Shirley Chung

Shirley ChungAlthough adoptees have been left in the lurch for decades, Emily Howe, a civil and human rights attorney who has worked with adoptees in the US, believes it’s simply a case of political will that needs to unite people across the political spectrum.

“This should be a clear fix: Adopted children should be equal to their biological siblings of parents who were US citizens at the time of birth,” Ms Howe said.

“The applicants have two, three or four US citizen parents and are now in their 40s, 50s and 60s. We’re talking about babies and toddlers who have been sent abroad through no fault of their own and are legally admitted under US policy,” she added.

“These are people who were literally promised that they would be Americans when they were two years old.

Shirley wishes she could get the President of the United States in a room so she and others like her can explain their stories.

“I would ask him to show some compassion. We are not illegal aliens,” she said.

“We were put on planes as tiny little babies. Just please hear our story and please fulfill the promise that America made to every single one of the babies that got on those planes: American citizenship.”