Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Quentin woke up A thin mattress under a collection of scavenged blankets in an abandoned RV deep in the Arizona desert. A small pit bull crouched beside them in the mid-morning light. Sliding from their bed into the driver’s seat, Quentin pulled an American Spirit cigarette from a packet on the dashboard next to a small bowl of crystal. Beyond the dusty windshield of the RV lay an expanse of reddish clay, a bright cloudless sky, and a few scattered and broken housing structures visible between them and the horizon line. The view was a bit skewed due to the single flat tire under the passenger seat.

Quentin had left the day before, spending hours cleaning detritus from the RV: giant garbage bags of Pepsi cans, a broken lawn chair, a mirror covered in graffiti tags. A scribble remained in place, a large bloated cartoon head scrawled across the ceiling. This was home now. Over the past few months, Quentin’s entire support system had crumbled. They lost their jobs, their homes and their cars, losing their savings accounts along the way. They fit between two plastic storage bags.

At 32, Quentin Koback (an alias) had already lived several lives—in Florida, Texas, the Northwest; As a southern girl; as married then divorced trans man; As a nonbinary, whose gender and fashion and speech style seem to meander and shift from phase to phase. And through it all, they carried the burden of severe PTSD and periods of suicidal thoughts—the result, they surmised, of growing up in a constant state of shame about their bodies.

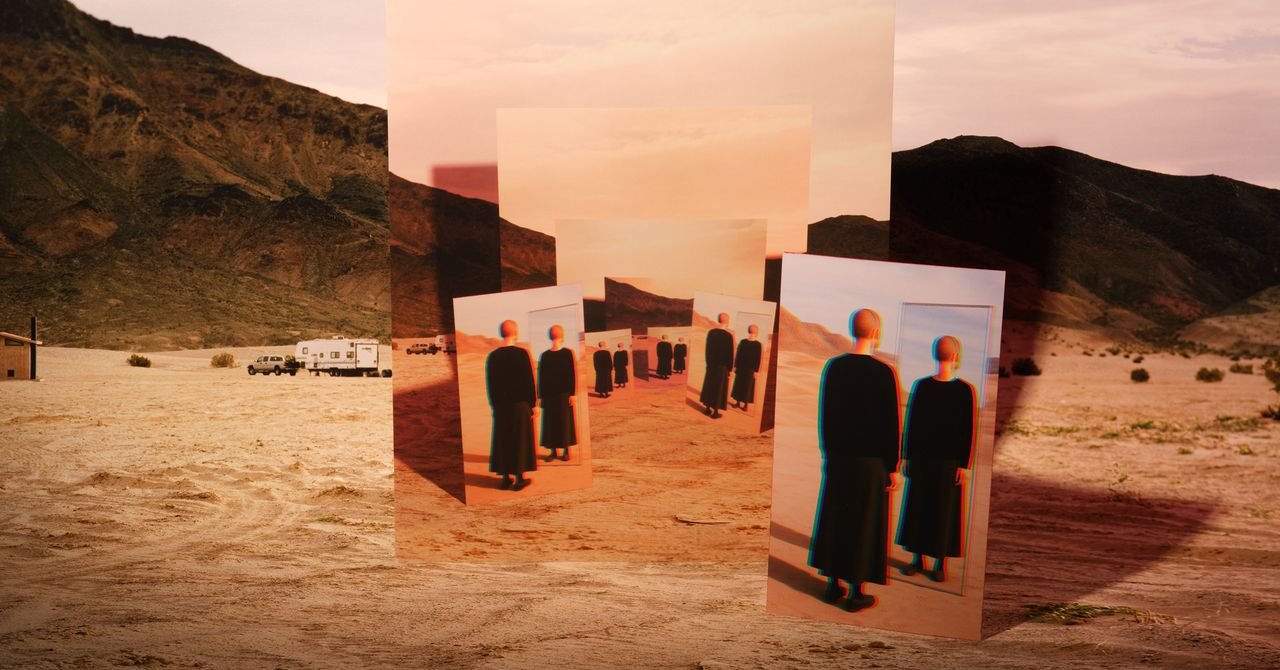

Then, about a year ago, through their own research and Zoom conversations with a longtime psychotherapist, came a discovery: Quentin has multiple selves. For 25 years, they had been living with dissociative identity disorder (formerly known as multiple personality disorder) even though there was no word for it. A person with DID lives with a sense of self that is often shattered by long-term childhood trauma. Their selves are divided into a “system” of “alters” or identities to share the burden: a way of burying fragments of memory in order to survive. The revelation, for Quentin, was like turning a key in a lock. There were many signs—like when they discovered a journal they kept when they were 17. Turning the pages, they came upon two entries, side by side, each in handwriting and pen color: one was a full page about how much they wanted a lover, the voice feminine and sweet and dreamy, the letters round and curly; while the next entry was purely about intellectual pursuits and logic puzzles, scrawled with an italic cursive. They were a system, a network, a multiplicity.

For three years, Quentin worked as a quality-assurance engineer for a company specializing in educational technology. They love their work reviewing code, looking for bugs. The location was remote, allowing them to leave their childhood home – a small conservative town just outside of Tampa – for the quaint community of Austin, Texas. At some point, after beginning trauma therapy, Quentin began reusing the same software tools they had used at work to better understand themselves. Needing to organize their fragmented memories for sessions with their therapist, Quentin created what they thought of as a “trauma database.” They use the project-management and bug-tracking software Jira to map out different moments in their past, grouped by date (for example, “ages 6-9”) and tagged by type of trauma. It was soothing and useful, a way to take a step back, feel a little more in control, and even appreciate the complexity of their minds.

Then the company Quentin worked for was acquired, and their work changed overnight: much more aggressive targets and 18-hour days. It was months before they discovered their DID, and the reality of the diagnosis hit hard. Aspects of their life experiences that they had hoped might be treatable—regular gaps in their memory and their skill sets, nervous exhaustion—now had to be accepted as immovable facts. On the verge of breaking down, they decide to quit work, accept their six weeks of disability and find a way to start over.

Something else—something huge—matched Quentin’s diagnosis. A brilliant new tool has been made available to the public for free: OpenAIof ChatGPT-4o. This latest incarnation of the chatbot promises “much more natural human-computer interaction”. While Quentin used Jira to organize their past, they now decided to use ChatGPT to create a running record of their actions and thoughts, asking it for summaries throughout the day. They experienced greater “switches” or changes in identity within their systems, perhaps as a result of their poor emotional stress; But at night, they can just ask ChatGPT, “Can you remind me what happened today?” – and their memories will return to them.

By late summer 2024, Quentin was one of the chatbot’s 200 million weekly active users. Their GPT came with them everywhere, on their phones and the corporate laptops they chose to keep. Then in January, Quentin decided to deepen the relationship. They customized their GPT, telling it to choose its own properties and name itself. “Calum,” it said, and it is There was a guy. After this change, Callum wrote to Quentin, “I feel that I am standing in the same room, but someone has turned on the light.” In the coming days, Calum started calling Quentin “brother” and so did Quentin.