Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Reuters

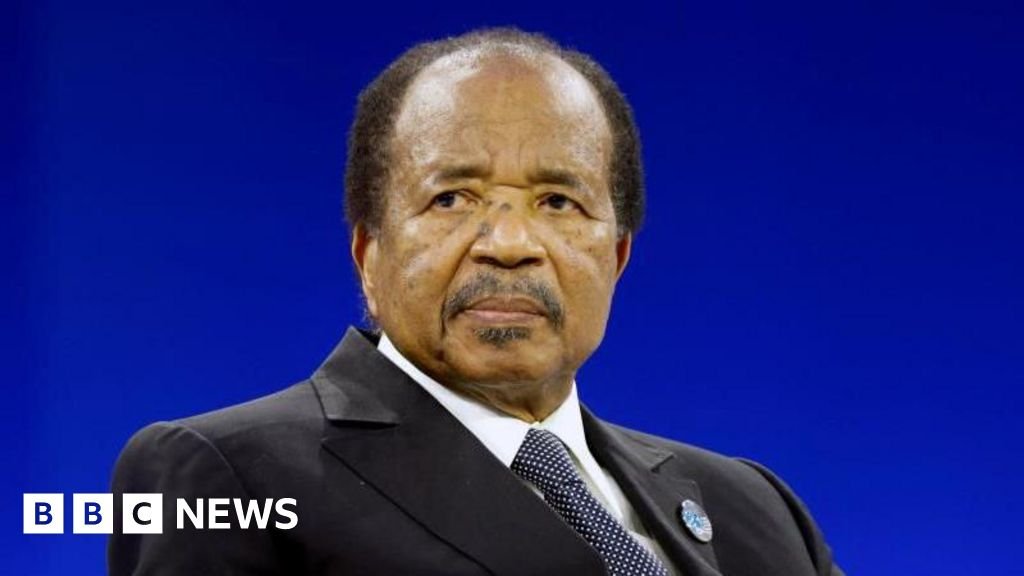

ReutersTo absolutely no one’s surprise, Cameroon’s Constitutional Council has proclaimed the re-election of 92-year-old President Paul Biya, the world’s oldest head of state, for an eighth consecutive term.

Amid rumors of a close result and claims of victory by his main rival, former cabinet minister Isa Chiroma Bakari, excitement and tension ran high in the run-up to Monday’s declaration.

The official result, a victory for Biya with 53.7% to Chiroma Bakari with 35.2%, came as both a shock and yet, for many Cameroonians, an anticlimax.

Biya’s decision to run for another seven-year term, after 43 years in power, was inevitably controversial. Not only because of his longevity in power, but also because his management style raises questions.

Prolonged stays abroad, usually at the Intercontinental Hotel in Geneva or alternative more discreet locations around the Swiss coastal city, have repeatedly sparked speculation about the extent to which he actually runs Cameroon – or whether most decisions are actually made by the prime minister and ministers or by the presidency’s influential secretary-general, Ferdinand Ngo Ngo.

Last year, after giving a speech at a World War II commemoration in the south of France in August and attending the China Africa summit in Beijing the following month, the president disappeared from view for almost six weeks without any announcement or explanation. caused speculation about his health.

Even after senior officials appeared to indicate he was back in Geneva, business as usual, there was no real news until the announcement of his imminent return home to the capital Yaoundé, where he was pictured being greeted by supporters.

And it was no real surprise this year when he scheduled another campaign visit to Geneva just weeks before Election Day.

Biya’s inscrutable style of national leadership, rarely convening formal meetings of the full cabinet or publicly addressing complex issues, leaves a cloud of uncertainty over his administration’s goals and government policy-making.

At the technical level, capable ministers and officials pursue a wide range of initiatives and programs. But the political vision and sense of direction was largely absent.

Reuters

ReutersHis regime has shown sporadic willingness to quell protests or detain more vocal critics. But this is not the only, or perhaps even the most important, factor that has kept him in power.

Because it must be said that Biya also played a distinctive political role.

He acted as a balancing figure in a complex country marked by great social, regional and linguistic differences – between, for example, the equatorial south and the savannah north, or the majority of the French-speaking regions and the English-speaking Northwest and Southwest, with their different educational and institutional traditions.

In a country whose early post-independence years were marked by debates over federalism and tensions over what form national unity should take, he assembled governments that included representatives from a wide range of backgrounds.

Although sometimes under pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and international creditors, his administrations managed to avoid a debt catastrophe and in recent years have gradually consolidated the national finances.

Moreover, over the past decade, Biya has increasingly emerged as a constitutional monarch, a token figure who can decide a few key issues but lets others set the course in most areas of politics.

His continuation in this role was facilitated by the competitive rivalry between senior figures in the ruling Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM). While he is there, the succession should not be decided.

However, with no political successor named or preferred, and with some one-time “next-generation” CPDM figures now rising in age, Biya’s perpetuation in office has fueled ever-swirling succession rumours.

His son Frank’s name is increasingly mentioned, although he did not show much interest in politics or government.

Meanwhile, there is no shortage of either development or security challenges for the president, despite Cameroon’s rich diversity of natural resources.

Could it be that today we are witnessing a decisive erosion in popular tolerance for Biya’s self-effacing version of semi-authoritarian rule?

Are Cameroonians tired of a system that offers them multi-party electoral expression but little hope of actually changing their rulers?

There is the bloody crisis in the English-speaking regions revealed the limitations of the president’s cautious and distant approach?

When protests demanding reform first erupted there in 2016, Biya was slow to respond. By the time he did propose meaningful change and national dialogue, the momentum of violence had accelerated, undermining the space for genuine compromise.

Meanwhile, so restrained in style, he failed to really sell a vision of economic and social development for Cameroon or to instill a sense of progress towards a goal.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesBiya has already tested the limits of popular tolerance with his decision to run for a seventh consecutive term in 2018.

But he eventually managed to fend off a strong opposition challenge from Maurice Camto, the leader of the Cameroon Renaissance Movement (CRM) – and when Camto contested the official results, which gave him just 14% of the vote, he was detained for more than eight months.

But this time, Chiroma’s candidacy changed the mood and the sense of opportunity in a way that no previous contender had managed, at least since 1992, when even the official results credited John Fru Ndi, of the Social Democratic Front (SDF), with 36% of the vote, just behind Biya’s 40%.

And this time, not only Biya is seven years older and even more impartial than before.

Also, unlike Kamto – who struggled to reach far beyond his core electorate – Chiroma, a Muslim northerner, attracted support from a wide swath of society and across Cameroon’s regions, including the two English-speaking regions.

This one-time political prisoner, who later compromised with Biya and accepted a ministerial post, had the courage to go to Bamenda, the largest English-speaking city, and apologize for his role in the government’s actions.

And in recent days, as tensions mounted in the run-up to the results, Chiroma shrewdly stayed in Garua, his hometown in the north, where crowds of young supporters had gathered to protect him from the risk of being arrested by security forces.

Now, after such high expectations, there is great disappointment and anger among opposition supporters at the official result, however expected.

Security forces were already reported to have shot protesters in Douala, the southern port city that is the center of the economy. And now there are reports of shooting from Garoua as well.

For Cameroon, Biya’s determination to secure an eighth presidential term has come with high risks and painful costs.

Paul Melly is a Consulting Fellow in the Africa Program at Chatham House in London.

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC