Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Mark PoyntingClimate and science reporter, BBC News

Naomi Ochwat

Naomi OchwatWhen an Antarctic glacier was caused to rapidly retreat three years ago, it left scientists scratching their heads as to what might have caused it.

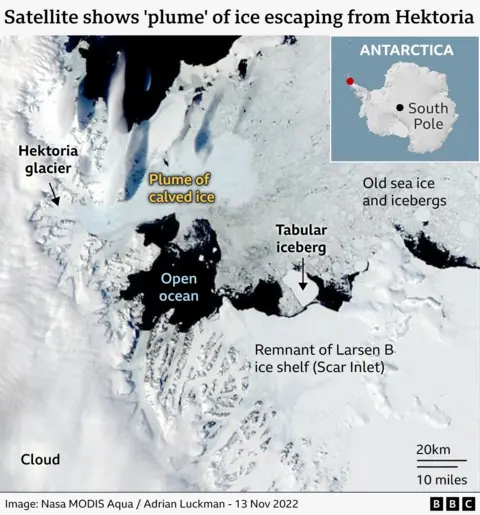

The Hectoria Glacier retreated more than 8km (5 miles) in just two months at the end of 2022 – and now a new study claims to have the answer.

The authors believe that Hektoria may be the first modern example of a process in which the front of a glacier lying on the sea floor rapidly destabilizes.

That could lead to much faster sea-level rise if it happened elsewhere in Antarctica, they say.

But other scientists argue that this part of the glacier actually floated in the ocean – so while the changes are impressive, they’re not that unusual.

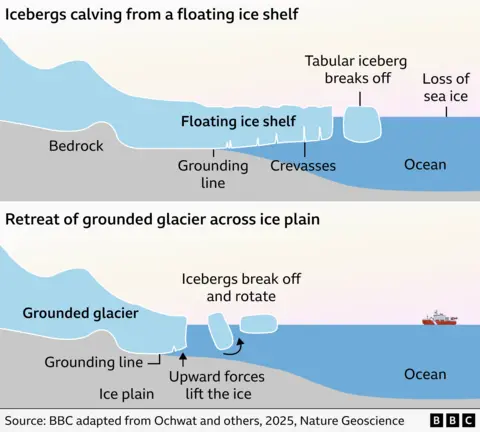

The floating tongues of glaciers extending out to sea – called ice shelves – are much more prone to breaking up than the fronts of glaciers lying on the sea floor.

This is because they can be more easily eaten by warm water below.

That Hectoria has undergone a tremendous change is not disputed. Its front retreated by about 25 km (16 miles) between January 2022 and March 2023, satellite data showed.

But unraveling the causes is like a “whodunnit” mystery, according to the study’s lead author Naomi Ochwat, a research affiliate at the University of Colorado Boulder and a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Innsbruck.

The case began back in 2002 with the extraordinary collapse of an ice shelf called Larsen B in the eastern Antarctic Peninsula. About 3,250 square kilometers (1,250 sq mi) of ice shelf was lost, roughly the size of Cambridgeshire or Gloucestershire.

Larsen B was effectively holding back Glacier Hectoria. Without it, Hector’s movement sped up and the glacier thinned.

But the bay vacated by the ice shelf eventually filled with sea ice “anchored” to the sea floor, which helped partially stabilize Hectoria.

That was until early 2022, when the sea ice broke up.

British Antarctic Survey

British Antarctic SurveyWhat followed was further loss of floating ice from the front of Hectoria as large flat-topped icebergs broke off or “calved” and the ice behind them accelerated and thinned.

This is not unusual. Iceberg calving is a natural part of ice sheet behavior, although it is man-made climate change making the loss of ice shelves much more likely.

What is unprecedented, the authors say, is what happened in late 2022, when they suggest the glacier front was “grounded” — resting on the sea floor — instead of floating.

In just two months, Hektoria retreated by 8.2 km. That would be nearly ten times faster than any land-based glacier previously recorded, according to the study, published in Nature Geoscience.

The authors say this extraordinary change may be due to an ice plain – a relatively flat area of bedrock on which the glacier gently rests.

Upwelling forces from ocean water could “lift” the thinning ice essentially all at once, they say — causing icebergs to break off and the glacier to retreat rapidly.

“Glaciers don’t usually retreat that fast,” said co-author Adrian Luckmann, professor of geography at Swansea University.

“The circumstances may be a bit specific, but this rapid retreat shows us what can happen elsewhere in Antarctica, where glaciers are slightly grounded and sea ice is losing its grip,” he added.

What makes this idea even more enticing is that this process has never been observed in the modern world, the authors say. But seabed markings suggest that it may have caused a rapid loss of ocean ice in Earth’s past.

“What we’re seeing in Hectoria is a small glacier, but if something similar happens in other areas of Antarctica, it could play a much bigger role in the rate of sea-level rise,” Dr Ochwat said.

This may include Thwaites – the the so-called “Doomsday” glacier. because it contains enough ice to raise global sea levels by 65 cm (26 in) if it melted completely.

“It’s really important to find out whether or not there are other ice sheets that would be susceptible to this kind of retreat and calving,” Dr Ochwat added.

But other researchers disputed the study’s findings.

The controversy is over the position of the “grounding line” or “grounding zone” – where the glacier loses contact with the sea floor and begins to float into the ocean.

“This new study offers a tantalizing glimpse into what could be the fastest rate of retreat ever observed in modern Antarctica,” said Dr Fraser Christie, glaciologist and senior earth observation specialist at Airbus Defense and Space.

“But there is considerable disagreement in the glaciology community about the exact location of the Hectoria Glacier grounding line because it is so difficult to get accurate radar satellite records of this fast-flowing region,” he added.

The location of the ground line may sound trivial, but it is extremely important to determine if the change is truly unprecedented.

“If this section of the ice sheet was actually floating (rather than lying on the seabed), the main point would instead be that icebergs broke off from the ice shelf, which is a much less unusual behaviour,” said Dr Christine Batchelor, senior lecturer in physical geography at Newcastle University.

“I think the proposed retreat mechanism and rate is plausible in Antarctic ice sheet settings, but because of the uncertainty about where the Hectorian grounding zone was located, I’m not entirely convinced that this is what was observed here,” she added.

But where there is little debate is that the fragile white continent – once thought to be immune from the effects of global warming – is now changing before our eyes.

“While we disagree about the process leading to this change in Hektoria, we fully agree that the changes in the polar regions are frighteningly fast, faster than we expected even a decade ago,” said Anna Hogg, Professor of Earth Observation at the University of Leeds.

“We need to collect more data from satellites so we can better monitor and understand why these changes are happening and what their implications are (for sea level rise).”

Additional reporting by the Visual Journalism team