Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Ayo Bello / BBC

Ayo Bello / BBCAs women water vegetables and pull weeds in a rural corner of northeastern Nigeria, men in uniforms stand nearby holding huge rifles.

They are the Agro Rangers, a special security unit set up by the government to protect farmers from militants from the jihadist groups Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province (Iswap), who can attack farms in Borno state at any time.

“There is fear – we fear for our souls,” Aisha Issa, 50, told the BBC as she tended her crops.

Since it is no longer safe for her family to live in the home they fled 11 years ago, she and many others like her are bussed to Dalwa village from a pick-up point in the state capital Maiduguri early in the morning. It is less than an hour’s drive away.

She now lives in temporary housing and growing beans and corn remains the only way she can feed her family, she says.

“We’ll take the risk and come even if the rangers don’t come.”

Here, the military has marked out a plot of land surrounded by clearly defined trenches where people can plant their crops. If they dare cross that border, the threat from Boko Haram is great.

“We hear that people are being kidnapped,” said 42-year-old Mustafa Musa. “Some have been killed. That’s why I’m afraid and don’t want to come unguarded.”

The father of 10 says he left his village of Konduga 13 years ago and will not settle there until the government provides lasting security.

In the 15 years since the Islamist insurgency began in northeastern Nigeria, thousands of people have died and millions have been forced from their homes.

The number of people killed in targeted attacks on farmers this year has more than doubled since 2024, according to research by the Armed Conflict Location and Data Monitoring Group (Acled).

Yet the governor of Borno state is speeding up the reintegration of displaced people from the camps back to the land – as part of his stabilization program and to counter disruptions in food production.

Kayla Hermansen

Kayla HermansenAlmost four million people face food insecurity in Nigeria’s north-eastern conflict zones, the UN has warned. But some aid agencies say the relocation of farmers to promote agriculture has been done too quickly.

The International Crisis Group, a non-profit organization focused on resolving deadly conflicts, says the policy puts internally displaced people at risk – stressing that militant groups extort farmers in areas they control to raise funds for their violent extremism.

Kidnapped along with nine other farmers and still terrified long after the ordeal, Abba Mustafa Muhammad has seen first-hand what happens when victims don’t pay.

“There was one who was killed because he couldn’t pay the ransom. His family couldn’t meet the deadline,” says Mr Muhammad. “He was killed and dumped. They asked the family to come and collect the dead body.”

Being a prisoner in a dense forest for three days was “unbearable”, he says. “The small meals they prepared often made us feel hungry and gave us diarrhea. There was no clean drinking water.”

The father-of-three told the BBC he was too afraid to return to subsistence farming because “the rebels are still lurking. Just yesterday they kidnapped over 10 people”.

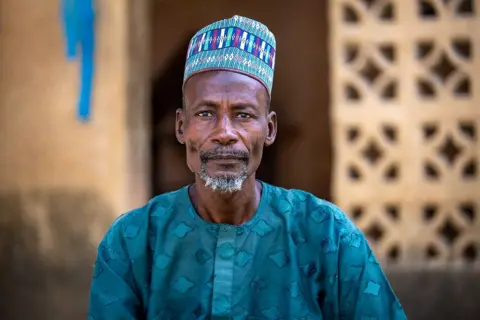

Ayo Bello / BBC

Ayo Bello / BBCDespite stories like these, Mohammed Hassan Agalama, the commander who runs the Agro Rangers scheme in Borno, insists that security is deterring militants from launching violent attacks.

“We have not seen more terrorists coming to attack farmers because they know we are fully on the ground during the farming season,” said Cdt Agalama, who works under the Nigerian Security and Civil Defense Corps (NSCDC).

James Bulus, a spokesman for the NSCDC, claimed the government was making gains in its fight against the insurgents, telling the BBC: “Only the harvest is there to tell you that normalcy is back and farmers are doing their normal farm business.”

However, he admits that resources are insufficient.

Agro Rangers is a small-scale project, not a long-term solution to widespread regional insecurity.

“We cannot be everywhere. We are not ghosts. Can 600 armed agro rangers cover all the farms in Maiduguri? No.”

It is for this reason that the Federal Government of Nigeria says it plans to expand the Agro Rangers scheme.

Acled’s senior analyst for Africa, Lad Serwat, says this year has seen a spike in the number of reported civilian casualties due to targeted attacks on farmers by armed groups.

Also, in the first half of 2025, reported killings by Boko Haram and Iswap reached their highest level in five years.

Ayo Bello / BBC

Ayo Bello / BBCIn downtown Maiduguri, a group of farmers gather at the home of Adam Goni, chairman of the Borno branch of the National Association of Sorghum Growers, Processors and Traders.

Men sit on rugs under the broad branches of a tree, while two women sit on mats in the shade of a nearby veranda, while goats and chickens roam the compound.

The entire group’s lives have been irrevocably changed by violence.

Among them is Baba Modu, whose 30-year-old nephew was shot dead on his farm by Boko Haram.

“It hurts a lot,” he says. “They killed people like an ant, with no remorse. The killings we experienced were devastating, but this year is the worst. When I go to the farm, there is a constant threat of being killed. I have no peace even at home – I often sleep with my eyes open, feeling that we might be attacked.”

Mr. Modu sometimes sinks into his chair, pausing in deep contemplation. He says the constant uncertainty weighs heavily on him and the community.

“Even if you’re starving and food is scarce, you can’t go to the farm. When we try, they chase us away or even kill us. At first they wanted a ransom when they kidnapped someone, but now they collect the money and kill the person they kidnapped again.”

Many farmers, like Mr Modu, say the militants can outnumber and overwhelm the Nigerian army when they attack.

“Sometimes even the security personnel run away when they see the rebels,” he adds.

On one side of the compound, Mr. Goni tends a potato bed.

He tells the BBC he has 10 hectares (24 acres) of land ready for harvest 8 kilometers (5 miles) away, but is terrified to harvest his crop.

The owner of the neighboring farm was murdered on his land just weeks ago.

“There is no safety. We just take risks to go there because when you go to farm, these Boko Haram people are there,” he says. “If you’re unlucky, they’ll kill you.”

Mr Goni believes the military can do more to end the conflict.

“We are very angry. We are unhappy with what is happening. If the government is serious, within a month Boko Haram will be finished in Nigeria.”

Meanwhile, the NSCDC’s Mr Bulus says the military is dealing with the wider conflict.

“Peace is gradual. You can’t achieve it in a day. It has to go through so many processes.”

But the process took too long for these farmers. More than 15 years later, uncertainty continues to plague every aspect of people’s lives.

The BBC asked the Nigerian army about claims by the farming community that it had not done enough to protect them, but it has yet to respond.

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC